I went back through the history of my blog the other day and reflected on how the contents of my blog have shifted over time. When I started my first WordPress blog in high school, it was a place for me to share unique interests (at that time, film cameras and photography) on the internet because my friends and family weren’t necessarily interested in the intricacies of what I was learning or doing. As I outgrew WordPress (literally, I hit my data limit and couldn’t post anymore), I turned to this space to continue documenting my thoughts, experiences, and interests. The value of this private-public space for me was in the openness I had in sharing myself with the possibility, but not the expectation, that someone I know would end up reading what I put out.

Over time, as it became more clear to me that people were actually reading, I began to be warier of what I shared here. I didn’t want to share thoughts or projects that weren’t “complete”, even though that’s what I had been doing for years before. I wanted to provide bulk updates on things that I was doing as if that could replace actually catching up with people. I shared more about actions and less about thought, perhaps because I thought actions and photos would be more interesting for the casual browser than thousands of words about really random trains of thought. My point is that I’m making a conscious return to treating this space where I entertain my own thoughts, formatted for the occasional friend or stranger to stumble upon and fall into if they find it interesting. Whether you’re a friend, family member, coworker, or stranger—you are free to dive in or wander away.

I’ve been thinking about clothes a lot lately, which is both strange and normal if that makes any sense. I have a very complex relationship with clothing. On one hand, I love a lot of things about clothes. As someone who is fascinated by how things are made, I love understanding and studying materials and fabrics and how small differences in manufacturing can lead to differences in end look, feel, and quality. As a photographer and designer, I can be obsessive about colors, tones, and textures. As a sewing enthusiast, the shape, cut, and drape of materials are details that I am naturally drawn towards. While all of these things are true, I’ve been dissecting a sense of shame that I feel in my admitted interest in fashion.

Why do I feel shame? A lot of people are into fashion. It’s a 3,000 billion dollar global industry. After a couple of months of thinking, I’ve broken my sense of shame down to a couple of factors.

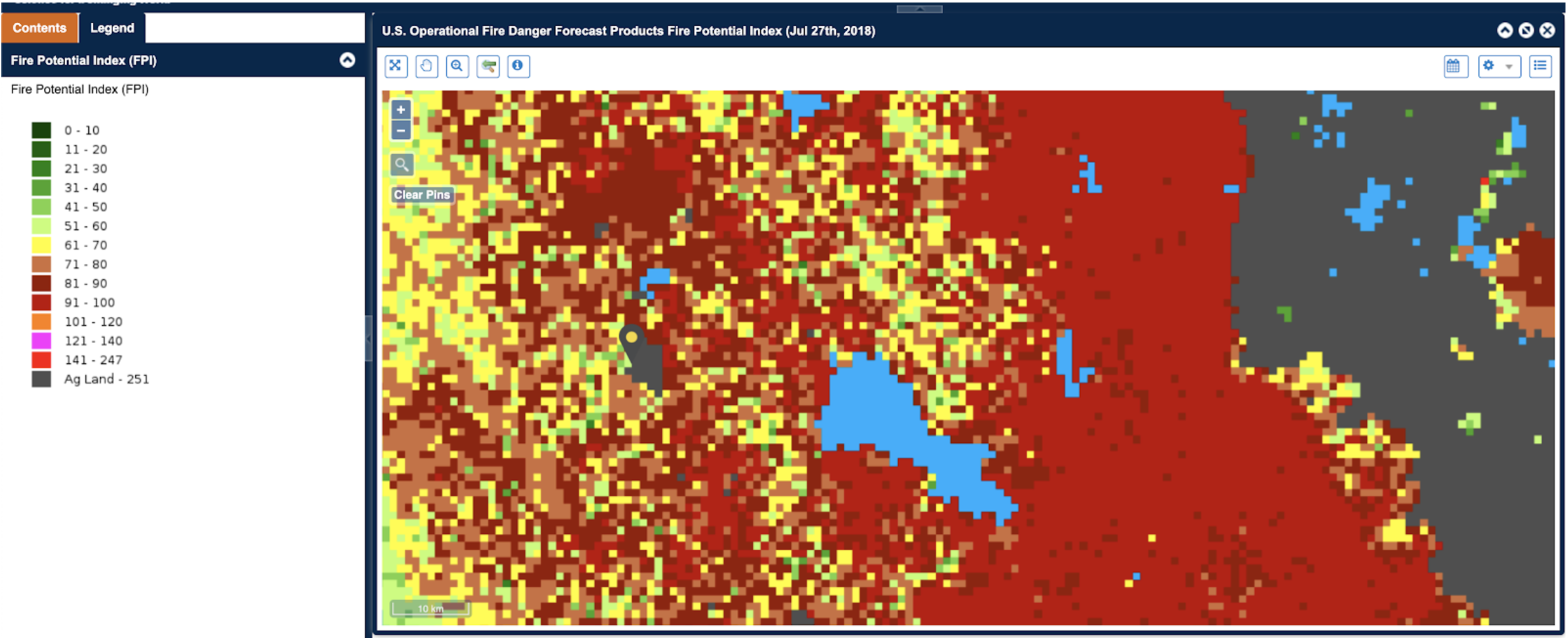

The most immediate sense of self-disappointment probably comes from the fact that clothes are horrible for the environment. I actually wrote pretty extensively about it here. Dressing all the people on earth is a significant contributor to climate change, and as someone who experiences anxiety about climate change and actively cares about improving our global fate, it can be hard to mentally balance the interest and the known environmental cost of that interest. Yes, there are ways of reducing impact by buying second-hand or buying ethically (however you want to define that) produced goods. Not all clothes are made like disposable fast fashion, but at the end of the day, every material thing has an environmental cost.

Beyond the environmental cost, I think there is a part of me that considers interest in material things frivolous. I kind of wish I were only interested in expanding my intellect or doing good in the world as if that would somehow make me a more fulfilled or noble person. But however I may try, I cannot help that my passion for design, appreciation of detail, and aesthetic diligence make me painfully materialistic. Luckily for myself, I channel that energy towards a “quality over quantity” mindset because I also cannot stand visual clutter.

By far my hardest to dissect part of how I feel towards clothes, I’ve realized, stems from a complex journey with my relationship with gender norms in society. For as long as I can remember, I was considered a “tomboy”. I liked doing stereotypically boy things, like playing basketball and baseball, building LEGOs, rolling around in grass and dirt, and generally being quite active. I also really liked playing with stuffed animals and the color pink, but I don’t think that was often highlighted as part of my identity that others perceived. I wore my brother’s hand-me-downs and didn’t care at all. I always had my mom tie up my hair because I didn’t like it in my face. In elementary school, I was made fun of for only wearing sports sweats and hoodies. Kids said I dressed like a homeless person. By middle school, I was choosing my own clothes, which ended up just being straight-fit jeans, a white basketball camp t-shirt, a red hoodie, and white Nikes. I still remember those exact articles of clothing—I liked them because they felt substantial and high quality, and I thought they fit well. Sometime during 6th grade, a girl told me to stop getting my clothes out of the dumpster, which, in retrospect, was pretty traumatizing since I was making active decisions about what to wear. I was made fun of regularly for not having gone through puberty yet. I don’t remember ever actively trying to dress like a boy, but I have vivid memories of feeling exposed and self-conscious about my body when forced into a more “feminine” way of dressing. I hated ballet flats because they made my calves look huge (because they were! from all the hours I spent jumping for basketball!), but they were the only accepted dressy shoe for girls during the 2000s. I hated girl-specific shirts because they had a huge waist-to-hip flare, which didn’t reflect my body at the time and looked awkward and balloon-y. I hated girl’s jeans because they didn’t have real pockets and were completely impractical. I hated patterns of all kinds because it was visually overwhelming, and girls clothes had lots of floral patterns. I couldn’t express it at the time, so my preferences, in the end, were assumed to be because I wanted to dress like a boy, which wasn’t really true either, but boy clothes fitted my straight-shaped body better than whatever was happening at Forever 21, so I went with it.

As peer pressure mounted in middle school and high school, I continued to make attempts at figuring out my “style”, which was pretty much finding one article of clothing I liked and wearing it repeatedly until it fell apart. I wore my basketball team hoodie, black jeans, and Rainbow sandals for probably 3/4 of my time in high school. I honestly just tried to think about clothes as little as possible, while simultaneously recognizing that some items of clothing made me feel great, while others make me want to crawl out of my skin. Junior year, I got asked to Prom and had to figure out something to wear. After hours and hours of stressful shopping with my friends to no avail, I found this borderline inappropriately short, skin-tight red dress that I absolutely did not expect to like, but did. It was made out of a soft but substantial, silky material, and it made me feel confident when I wore it. My mom was alarmed at my dress choice (it is still the shortest, most revealing dress I have ever worn), as was most of the school when I showed up at Prom, but for some reason, it felt right to me. I would say, upon this reflection, that it was from that experience that I realized my distaste towards clothing was not about an aversion to being “feminine”, but about finding a relationship between material and form that fit my perception of myself.

By college, I had a bit of a clothing budget from side hustles and really began searching for a particular style. I bought H&M way more than I want to admit. I gravitated towards t-shirts with interesting details, like mesh panels or atypical cuts, and lots of gray/black/maroon. I ended up with a ton of clothes, most of which I never wore. I still couldn’t put into words what I was looking for at the time, but by end of sophomore year, I had a ton of monochromatic clothes of extremely shoddy quality. After having to pack all of my belongings and move them to a storage unit with a rental car myself in the pouring rain while battling the flu, I decided I couldn’t have so many things anymore. That summer, I discovered minimalist wardrobes and decided I would only wear 3 t-shirts and 1 pair of black jeans. I bought the nicest t-shirts and jeans I could reasonably afford, and I felt great about my clothes every day. It was pretty liberating. I returned to campus and sold the majority of my clothes on Poshmark or gave them to friends. I kept a couple of hoodies and jackets but weaned myself off of fast fashion. I was searching for freedom from the “I have so many clothes and none of it makes me feel good and I don’t know why” kind of feeling, and I solved it by getting rid of most of it and sticking to a formula. It worked. I rode through college wearing the same combination of the same black jeans, 3 t-shirts, skate shoes, hoodies, flannels, and winter jackets. It really was an evolution of my 6th-grade outfit, but by this point, I stopped trying to push the boundaries of what could make me feel good and focused on what did. I did discover at some point that black overalls and Dr. Martens made me feel very comfortable and embraced that.

When the consulting lifestyle rolled around and I realized I would have to have a business wardrobe, I did the same thing. I found one pair of dressy pants that I liked and bought them in 4 colors. I found one blouse that I liked and bought it in 3 colors. The silhouette was exactly the same every time, but I felt fine in it and it worked for the purpose. I was pretty deep in minimalism on YouTube by this point in my life and was obsessed with the idea of living out of one bag and only having one high-quality item of everything I owned. It suited my 300-square-foot studio life and the subsequent world traveling I did before returning home to California. I got really into technical fabrics like merino wool, which promised the ability to stay fresh after multiple days of wear. I became aware of travel-centric brands like Western Rise, Icebreaker, Smartwool, etc. The idea of having one outfit that I could wear indefinitely without drawing attention to myself was highly appealing.

When I moved back home to California, my wardrobe became a mashup of the items I had left behind when I moved to college and everything I had brought back from Boston. It was a pretty weird mashup of items—MIT track jackets, winter coats, merino wool shirts, my consulting outfits, random sweaters and basketball shorts from high school. I bought some clothes to try to fill the gaps — lots of Topo Designs stuff as I was going hiking more often and appreciated the outdoor vibe conceptually. That was pretty much what I’ve been wearing until I started taking a more structured approach to my wardrobe this year and feeling the urge to experiment again.

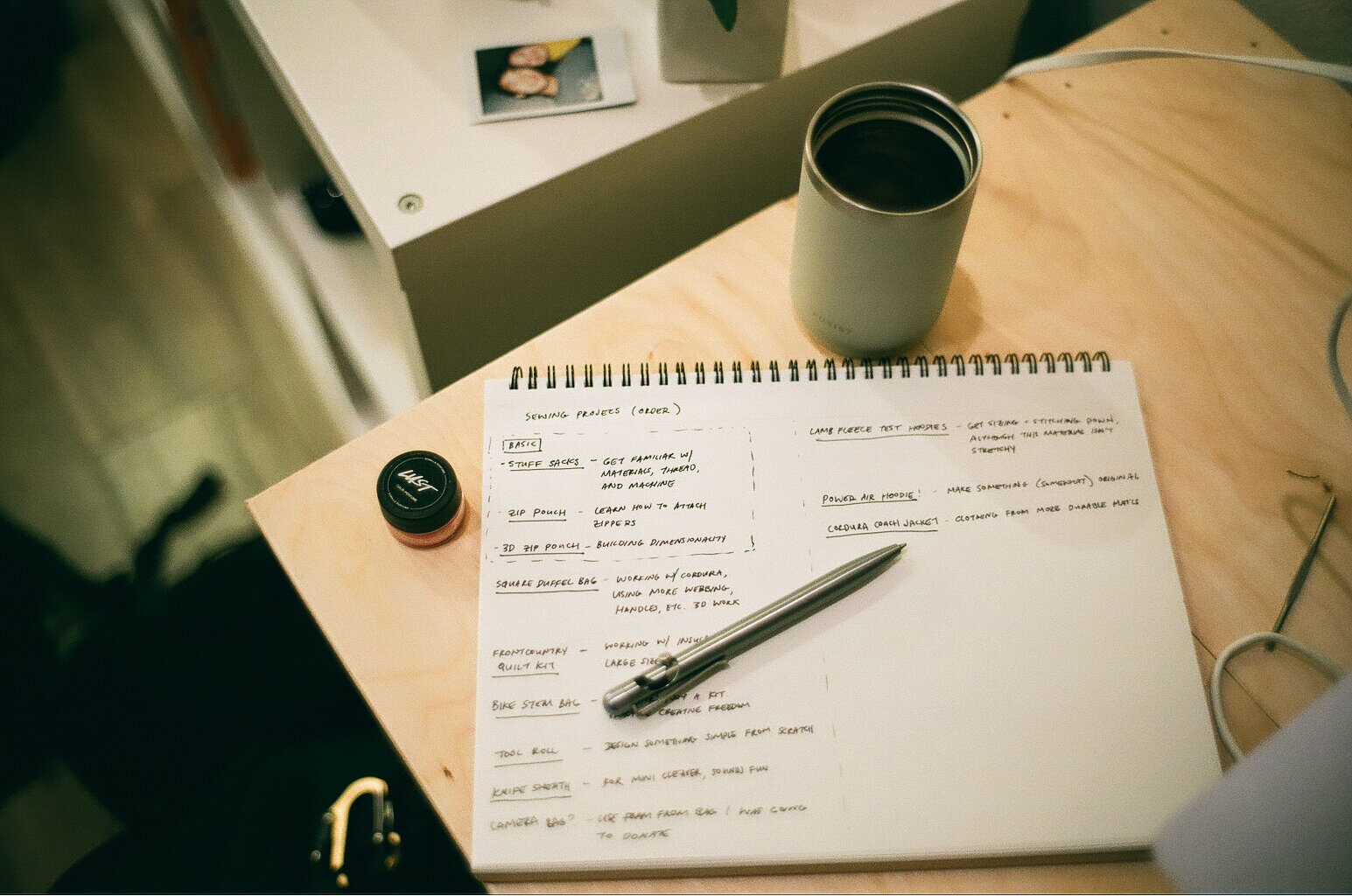

I’m not quite sure where that urge came from. I thought it was from the suffocation of COVID, but I still work remotely and don’t really go out other than on the occasional weekend. Maybe I feel my mortality and I want to pursue the things that invigorate me, especially something that happens on a daily basis. Maybe after sewing some complex projects, I have an even greater appreciation of quality and the subtleties of designing soft goods. Maybe it’s how I deal with the monotony of living in the suburbs during a pandemic and working from home. Maybe I’ve just finally figured out that I don’t have to be self-conscious about my aesthetic preferences and it’s fine to be into something frivolous. Really, I don’t know.

What I do know is that I now have a much better sense of what kinds of things I like. That includes monochromatic looks, utilitarian pieces, aesthetic minimalism, and material elegance. I really enjoy natural materials like linen and silk. I don’t like loud colors or visually complex articles of clothing because I get bored of them easily. I like chunky shoes because they make everyone’s feet look big so I don’t have to worry about my feet looking particularly big. I like Asian-inspired design, and a lot of Japanese brands appeal to me in their material quality and unique manufacturing. Whenever I have too much from one noticeable brand, I start feeling like a walking advertisement and I don’t like that. I like cropped tops and high-waisted pants because they fit my body proportions well. I like yellow and pink and warm earthy colors. My wardrobe is probably 50/50 on clothes explicitly designed for men vs women. Men’s pants tend to fit me better because the inseam is longer and I don’t have wide hips. Women’s tops tend to fit me better because I have narrow shoulders. I don’t always want to wear black but black suits me because I am a clumsy person and I always spill stuff on my clothes. I like mock necks because they make my neck look shorter, and sometimes I feel like a giraffe. I’ve learned that true minimalism is not for me, because I get bored of wearing the same thing every day and I like having things for specialized purposes, as long as it’s getting used (ie. I don’t want to run in my dress pants. I want my dress pants to be nice and sweat-free and I want my running pants to be good for running). It’s okay if all of my things don’t fit in a suitcase. Ultimately, I just want to be prepared enough to go into any situation and feel confident about how I look, so I can focus on the experience ahead of me rather than fearing that I’ll be uncomfortable or out of place.

After all this talk about clothes, were you expecting photos? I thought about putting some here to visualize my point but decided I had no desire to. Even though I have put an insane amount of time into figuring out a cohesive wardrobe, I genuinely feel like I did it for myself and don’t feel a need to share it publicly. And that’s kind of the point of this wandering post—a reminder to myself that even things that were once traumatizing (like getting dressed) can eventually be an enjoyable part of every day. The key, for me, was lots of reflection and intentionality.