guest post by max: lifecycle of a wildfire (part 1)

Living in California this year has been filled with all of nature’s torments. I haven’t been able to see friends because of COVID-19. Up until this past weekend, I hadn't gone outside all month because of awful wildfire smoke (it’s a relief to just crack open a window). And to top it all off, I’ve finally experienced my first earthquake (actually the first two!).

And with so much time indoors, I’ve dug into the only one of those disasters that has become regular, wildfires. I’ve read countless articles about each of the latest fires: Bobcat, SCU Lightning Complex, Glass, the list goes on. But these update articles feel like getting score updates to a sport that I don’t know the rules of. What does 15% containment mean for a fire? How does CalFire know when there’s a red flag warning in an area? How dangerous is a red flag warning? How quickly will a fire spread?

It’s with these questions in mind that I started writing this article. I always loved writing profiles when I was involved in high school journalism. Painting a portrait of a person with words, that’s how I imagined a profile. Being able to really tell a story, from start to end. That’s what I want to do with wildfires. That’s the idea, anyway. Tell the story of a wildfire, one wildfire, from start to finish.

With that goal in mind, I’ve pieced together the story of one wildfire, the Mendocino Fire Complex in 2018. I use that story to illustrate the life and death of wildfires in general. I try to answer the original questions I had, and a few more. My plan is to do it in three parts: ignition, spread, and containment. That plan may change as I find more interesting tidbits to share, but that’s the rough shape I have in mind now.

So why the Mendocino Fire? Well, up until just a couple of months ago, the Mendocino Fire Complex burned an at-the-time record 459,000 acres and lasted from July 27 to Sept 18 (53 days). The fire destroyed 257 structures, caused 257 million dollars in damages, and required 201 million dollars in fire suppression costs. While the Mendocino Fire Complex was giant for its time, it is only 35 miles away from the currently burning August Complex, also in Mendocino County, which is the newest largest California fire on record at over a million acres. It holds the infamous title of being the first and only California fire to grow larger than a million acres in recorded history.

Ignition

To set the scene, the Mendocino fire complex was actually two nearby fires, with the first one being the Ranch fire that started on July 27, 2018 at 12:05, and the second River fire starting about an hour after that. By the next morning, the two fires had already grown to nearly 10,000 acres and had destroyed two structures. The map below shows the extent of the spread.

https://wildfiretoday.com/2018/07/28/ranch-and-river-fires-burn-thousands-of-acres-in-mendocino-county/?hilite=%27mendocino%27

The two fires flanked the nearby town of Ukiah, with the Ranch fire to the north east and the River Fire to the south east. These fires were only about 8 miles away. The Mendocino County Sheriff’s office ordered mandatory evacuations pretty much immediately. The image below was the view from Ukiah the morning after the fire started.

https://www.lakeconews.com/index.php/news/57113-acreage-for-ranch-river-fires-grows-overnight

The crazy part of this looming disaster was the ignition source: the Ranch Fire started from a spark caused by a resident hammering a concrete stake into a wasp’s nest. The resident was identified by the NYT, based on public records, as Glenn Kile, a heavy equipment operator turned rancher in his mid-50s. I found the official narrative from the CalFire incident report fascinating, so here it is verbatim:

[Kile] said he was putting up a shade cloth for the above ground water tanks located up the hill from his residence. He said the shade cloth blew down sometime last year and he wanted to put it back up as a barrier from the sun. He said he was in the process of putting it up when he agitated an underground yellow jacket's nest. [Kile] said he is allergic to bees and waited for the yellow jackets to stop swarming. Once they did, he quickly hammered a 24-inch concrete stake into the ground to plug the hole. He said he used a claw hammer and drove the concrete stake 10 to 12 inches into the ground. [Kile] said he smelled smoke and saw a vegetation fire next to where he was working. [Kile] said the fire was 2 feet by 2 feet in size when he first saw it. He said the fire started in grass he estimated to be 2 to 3 feet in height. He said the vegetation fire moved quickly to the shade cloth located on the ground a few feet away. [Kile] grabbed a shovel and tried to extinguish the fire, but said the ground was so hard it was difficult to get enough dirt to be effective. [Kile] said he tried to use a black polyurethane waterline next to the water tanks to extinguish the fire, but the line kinked from the heat of the fire and restricted the waterflow. [Kile] then tried to use a 1½ inch PVC water line connected to the water tanks, but was unable to get enough water pressure to reach the fire. [Kile] said he unhooked the trailer from his four-wheeler and tried to get in front of the fire traveling uphill from the water tanks. He said in the process, he lost control of his four wheeler and had to jump off. The four-wheeler rolled downhill lodging itself between the water tanks and a cut bank. [Kile] said he ran downhill to his residence and called 911 to report the fire. He then turned on the water pump near his residence to supply the water tanks to help support the incoming fire suppression resources. At the time of the interview, [Kile] was suffering from what appeared to be smoke inhalation and heat exhaustion. [Kile] refused an ambulance and medical treatment.

Imagine the fear of going from fighting a wasp’s nest to fighting a fire. Imagine the frenzied attempt at putting out a fire, starting with a shovel in hard, baked dirt, to furiously attempting to start a waterline, to driving, then crashing, a 4 wheeler. Ultimately, Kile was found to be not negligent, though still responsible. It’s clear that it doesn’t take much to start a fire in the California grasslands.

The Mendocino Fire’s ignition source highlights a key wildfire concept called the probability of ignition, which is how likely a spark will ignite if it lands on potential fuels, like, in this case, dry grass. The four factors in this determination are shading percentage, temperature without humidity, the percentage of moisture in the fuel, and the “fineness” of a fuel. This data is summarized in the table below.

Looking back on historical weather data, on July 27, 2018 in Potter Valley, CA (near the fire), the low was 56 degrees F and the high was a scorching 107 degree F. To add on top of that, it hadn’t rained at all the entire month of July, and the grass had been drying out in the sun all summer, classifying it as a “fine dead fuel”. These conditions certainly put the probability of ignition of Kiles’ spark from a concrete stake into a wasp’s nest in the 70% plus range.

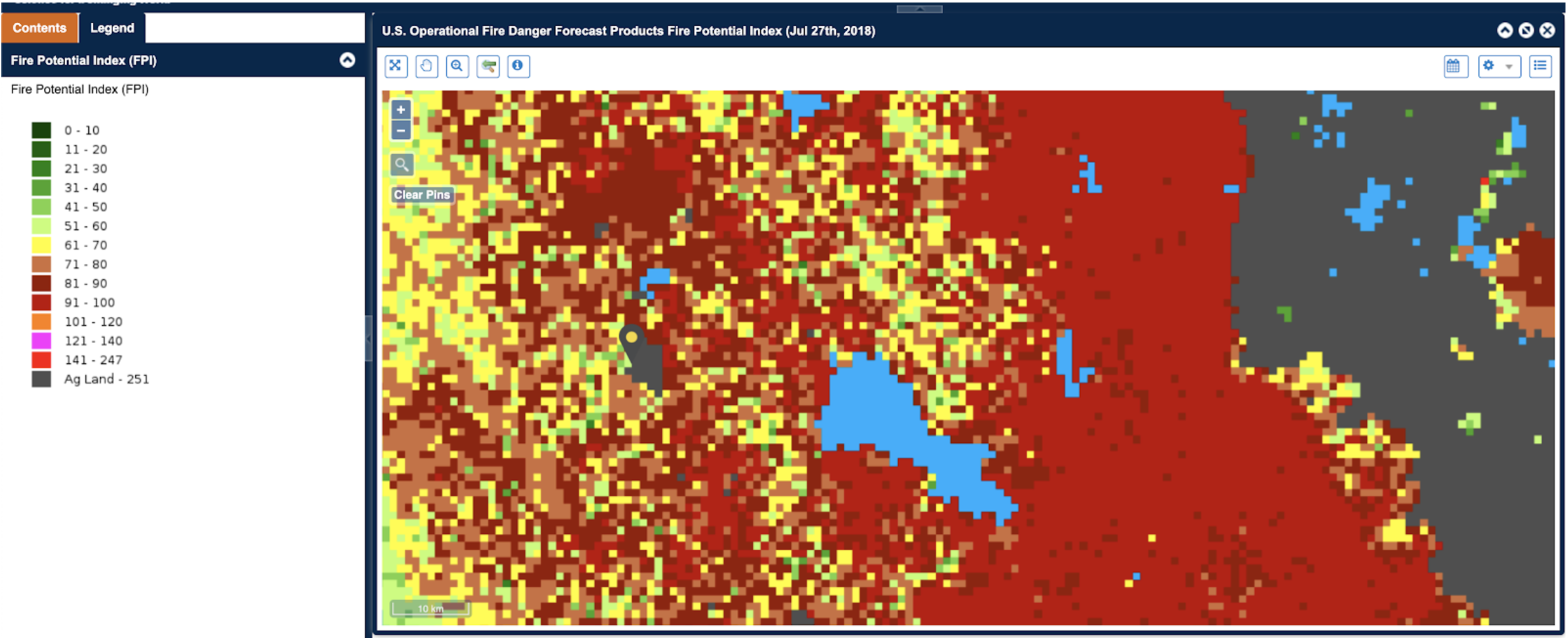

Another metric that tries to capture this same idea of fire danger is the Fire Potential Index (FPI). The FPI is really a measure of moisture levels, accounting for how flammable different kinds of fuel are at different moisture levels, and what percent of the vegetation is dead. The FPI is a value between 1 and 100, where 100 indicates the highest chance of starting a fire (very low moisture, and a lot of dead vegetation).

Using satellites, the greenness of an area is used to estimate the moisture level. Moisture levels are measured by comparing the dead fuel moisture, the moisture of dead grass / trees, to the moisture of extinction, the moisture level needed to stop a fire from spreading. The lower this ratio, the more likely a fire can start. The moisture of extinction varies by the type of fuel: grasses tend to have the lowest moisture of extinction, at around 15 percent, while trees are generally higher, in the 25 to 30 percent range.

The great part of the FPI is that the USGS has calculated it for every square kilometer of the US since 2001. If you want to find your neighborhood’s FPI, you can go here: https://firedanger.cr.usgs.gov/viewer/index.html and enter in your home address. The screenshot below shows the FPI in the area surrounding Ukiah on the day the fire started, with the pin indicating where Ukiah is located.

Scroll up and compare this to the map of the wildfire’s spread one day after the fire started, and you’ll see that the fire started in a sea of red. Conditions could not have been more ideal for a large wildfire. The solid red block to the east of the map also explains why the fire would expand eastward, in addition to the fire fighting resources that protected Ukiah and surrounding communities.

The conditions shown here also represent large parts of California’s grasslands. Limited rain during the summer and high temperatures (which are becoming more extreme weather due to climate change) drive up the probability of ignition and the fire potential. Add to this tinderbox the expansion of communities near wildland areas, and there’s a near certainty of human-caused fires spreading throughout the state.